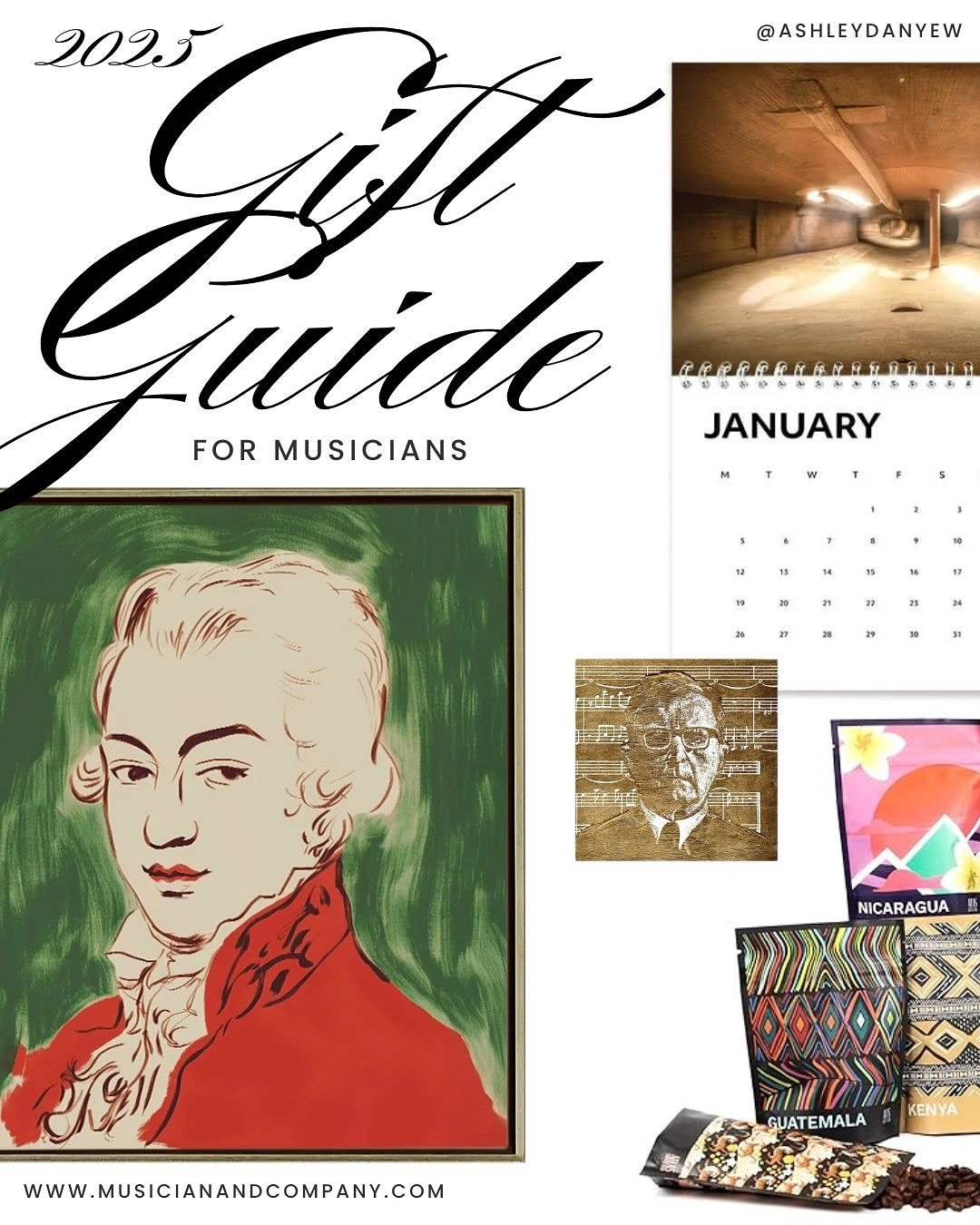

Resources Mentioned

*Disclosure: some of the links in this episode are affiliate links, which means if you decide to purchase through any of them, I will earn a small commission. This helps support the podcast and allows me to continue creating free content. Thank you for your support!

Developing Musicianship Through Improvisation, Book 1 (Azzara & Grunow)

A Systematic Introduction to Improvisation on the Pianoforte (Czerny)

Ep. 066 - A Winter Improvisation Prompt for Elementary Piano Students

Lyric Preludes in Romantic Style (William Gillock)

“Chromatic Monochrome” in Moving Pictures (Naoko Ikeda)

When I was in grad school, I took an elective class on Improvisation. I remember shuffling into the 3rd-floor classroom that first day, pulling a blue chair into the semicircle like everyone else, unfolding the desk and preparing to take notes.

Everyone was quiet. There was a palpable uncertainty among the group—all classical musicians by training. When had we ever been asked to improvise? No one wanted to be put on the spot.

We started by talking about where to start with improvisation. “Improvisation is something we can all do,” our professor, Dr. Christopher Azzara began. “We’re born improvisers.”

We know that improvisation was a common practice among performers throughout music history. J.S. Bach, Carl Czerny, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Felix Mendelssohn, Franz Liszt, Robert and Clara Schumann, and many others gave performances of entirely improvised pieces: preludes, fantasies, and ricercars. (source)

In fact, many of the compositions we have from this period originated as improvisations. As Drs. Azzara and Grunow, the authors of Developing Musicianship Through Improvisation explain, "Notation is the documentation of a creative process."

The challenge sometimes is trusting that creative process. Trusting that we have something interesting and musical to say.

Improvisation is a skill like anything else; it can be learned and developed. Of course, there’s safety in writing it down, but learning the fundamentals of improvising and giving yourself time to experiment and practice this can be really fulfilling, especially in teaching.

Today, I’m sharing a few simple ways to build improvisation into your teaching practice in meaningful ways, even if it’s new to you. You’ll learn what improvisation is and how to get started, how to find inspiration and musical ideas, and activities to do with your students in lessons. I’ll also share a few examples and recordings from my studio recently.

In his 1829 treatise, A Systematic Introduction to Improvisation on the Pianoforte, Carl Czerny noted,

“When the practicing musician possesses the capability not only of executing at his instrument the ideas that his inventive power, inspiration, or mood have evoked in him at the instant of their conception but of so combining them that the coherence can have the effect on the listener of an actual composition—this is what is called: Improvising or Extemporizing.”

There are a few things at work here.

First, the capability of executing ideas at your instrument instantly. This requires skill and technique, but also a connection between mind and body, the ability to understand and translate what you hear in your head into sound.

“Anything that is grouped can be improvised,” Dr. Azzara said in class one day. And it’s true. This is why it’s so important to learn rhythm and tonal patterns vs. focusing on individual notes. This is akin to grouping letters into words in language. At some point, you stop reading the individual letters and start reading familiar patterns, familiar groupings—words that become part of our vocabulary, to be used and built upon.

The second element of Czerny’s definition is that it must have the coherence of an actual composition. The patterns make sense together, there’s a logical progression or order to them. This again is a reflection of musical thought and understanding, perhaps even expressed as musical storytelling.

It’s a reflection of the musical ideas and vocabulary you’ve learned and internalized. “Improvisation,” Dr. Azzara said, “is the spontaneous expression of musical ideas.”

We collect musical ideas through the music we learn and engage with, through the repertoire we study. Dr. Azzara reminded us that learning repertoire is like learning stories. And paying attention to that, engaging with that, and being inspired by that gives us the freedom to be more articulate and thoughtful and create more meaningful interactions.

Student Example #1

I have a new 3rd-grade student who’s been taking lessons with me for about 9 months. She has a vivid imagination and a developed ear and will often explore patterns and ideas through musical storytelling. In her lesson last week, she spontaneously created a story about a mosquito and a hippo (based on a piece she’s learning in Piano Safari Book 1).

She narrated it for me as she played, “Now the hippo is mad, so he plays down here,” she said, playing slow, blocked intervals in the bass register. He has to get up here to be happy, she said, pointing to Treble C. “And the mosquito is flying around up here,” she demonstrated with a series of single staccato notes bouncing between the hands in the upper register.

Her improvisation was very loosely based on the repertoire she was learning, but she demonstrated her understanding of register, call and response, rhythm patterns, articulation, and musical character.

And that’s what it’s about, isn’t it? Providing the space to practice and apply what you’re learning. To explore register and dynamics, to repeat patterns and create new ones. To play.

One way to incorporate improvisation into your lessons is to build off an existing piece of repertoire. This could be creating your own version of the Bach Prelude in C (study J.C.F. Bach’s Solfeggio in D for extra inspiration). Building on a progression in a Mozart String Quartet. Reharmonizing a Christmas carol. Experimenting with a new version of Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1.

For beginning students, I love doing this with “Dandelion Fluff” in Piano Safari Book 1.

The student part is written in black-key pentatonic and has a lovely, flowing accompaniment. Once the student has learned the piece, I suggest they create their own version using black keys in the upper register. I may keep the accompaniment the same or interact with what I hear them doing. Most students are uninhibited by this prompt, and we often play it more than once before coming to a natural end.

Here’s an example from 12 weeks ago, with the student I mentioned a minute ago. Right after I hit “record,” she said, “Before we start, I want to figure out which notes I want to use.” She proceeded to play a series of seven blocked intervals—in a steady half-note rhythm—then said matter-of-factly, “Okay, I got it.”

I love that she took the time to make a few musical decisions ahead of time. This is an important part of the creative process—establishing structure, deciding what goes together. It’s like gathering ingredients before you start cooking. What do you want to make? What flavors will work well together?

Here’s her improvisation.

I love how much space she built into her improvisation—that’s often difficult for beginners. I also love her use of blocked intervals (a contrast from the notated version of the piece). The rhythm patterns she included demonstrate her understanding and ability to interact with my part.

This is a similar activity to the Snowflake Improv prompt I use with beginners during the winter. You can learn more about that and hear examples in Ep. 066.

Student Example #2

Another great way to use improvisation is to help students practice new skills. This could be ornaments, octaves, crescendi and decrescendi, dotted rhythms, Alberti bass, chords in inversion, or a new interval.

This was the invitation I offered a 4th-grade student one day. She had just finished playing “Metamorphosis” in Piano Safari Book 2, but before we checked it off and moved on, I said, “Can you make your own version?”

This student is usually a little more reserved when it comes to improvising. We talked through a few of the building blocks in the repertoire—pedal, rhythm patterns in diminution (moving from whole notes to half notes to quarters to eighths), and blocked and broken 5ths with thumbs one step apart. “What do you want to keep the same?” I asked. “What do you want to change?”

I find that much of improvisation starts with the words “what if”:

What if this pattern went up instead of down?

What if you played this as two long notes instead of four short ones?

What if you played this in minor instead of major?

What if you rearranged the order of notes in this pattern?

What if you substituted this chord for that one?

What if, what if, what if…

Here’s what she created.

I like that she chose to start in the middle register and began with broken intervals, then blocked (the opposite of the repertoire). I also like her inclusion of repeated notes and patterns in mirror image. She also added a new rhythm pattern in the middle that was not in the original, and wasn’t afraid to repeat patterns. Repetition is a fundamental component of music, but often, when creating, students feel the need to continue improvising new patterns all the time.

Student Example #3

One other way you can incorporate improvisation is by using it as a tool for students to explore a specific key area or tonality.

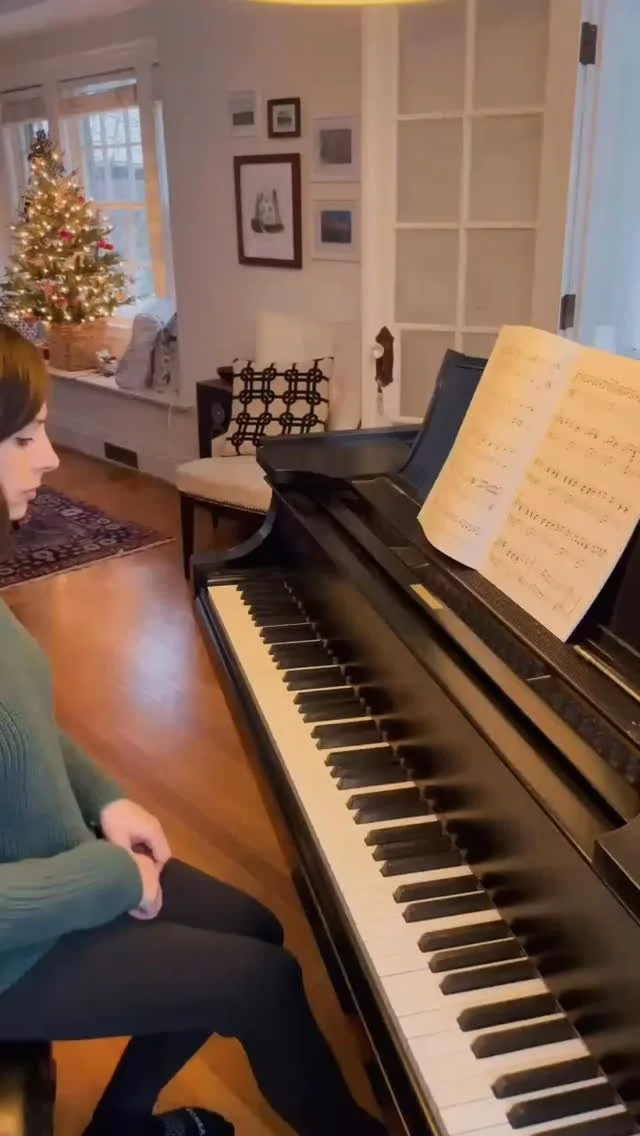

I do this with one of my high school students who loves to improvise. He often comes into his lesson and begins improvising right away as a way of warming up. He also creates his own modulations between pieces voluntarily—for instance, the first piece he plays is in D minor, and the next one I ask for is in G major—he’ll find a way to get from D minor to G major through chord-playing.

Last year, we were working on several pieces in William Gillock’s Lyric Preludes. When learning “Seascape,” I invited him to create an improvisation in the key of C minor, based on the ideas in the piece.

If you don’t know it, the original is marked by dramatic register shifts, strong dynamic contrasts, rapid repeated notes, low octaves, and dense triads.

Here’s his interpretation:

I enjoyed hearing the call-and-response ideas in the beginning, the contrast between the low octaves and the treble melody, and his use of repeated notes. As the improvisation progressed, he brought in more of the interplay between scale degrees 5 and flat-6 (from the original), and I also liked his use of blocked 3rds and single-line melodies—a contrast from the original.

In our lessons this summer, we’ve been working on “Chromatic Monochrome” by Naoko Ikeda. In addition to exploring a chromatic walking bass and jazz syncopations, we’ve talked about how the chord progression in the middle sounds like the James Bond Theme, which the student learned a few summers ago.

Inspired by a session I attended at the online NCKP conference earlier this summer, I asked my student to consider how he might use the chromatic bass line and improvise new material on top of it. Some elements could remain the same—the rhythm, a few melodic shapes, the 2-voice texture. Others could be varied or built upon—the articulation or intervals, melodic shapes, or rhythms. We analyzed the melodic material and realized it’s based on an A minor pentascale with the addition of a flat-5 (similar to the blues scale).

Once you have an understanding of how the music is made, you can begin to see (and hear) all the possibilities for engaging with it, building upon it, and creating from it.

8 Quick Ideas for Improvisation

If you’re looking for more inspiration, check out Ep. 036, where I share a story from the early days of my studio. In the meantime, here are 8 other quick improv ideas to try in your teaching:

Make a melody in collaboration with your student. Start with two notes, then have your student play back those two and add a third. Then, you play back those three and add a fourth. Continue until one of you can’t remember the sequence!

Have your student create a melody in a given key or 5-finger position to go with a rhythm exercise

Extend a sight-reading exercise by having your student improvise another 4-8 bars

Ask your student to create a piece in the style of another piece they know

Have your student create melodic or rhythmic variations for the lower part of “Heart & Soul”

Have students play musical patterns and sound effects to accompany a story. This is a great group activity!

Play a short cartoon and have students create their own musical accompaniment

Invite your student to create an alternate ending for their piece. What if it ended low instead of high? What if the ending was bold and strong or delicate and light? What if there was a musical surprise at the end?

Three Ways to Support & Encourage Improvisation in Your Students

In conclusion, I want to share three tips for supporting and encouraging improvisation in your students:

Offer an example or two. Show them what it looks like to create in the moment.

Give specific praise (e.g. “I loved how much space you included” or “I like how you chose to repeat that pattern, then do something different the third time”). I talk more about how to use praise with intention in Ep. 021.

Experiment with them. Try not to make it feel like a performance they’re being graded on. Improvise an accompaniment along with them or brainstorm ideas of patterns they could use.

I’d love to hear from you:

I hope this inspires you to explore improvisation in your own practice. I’d love to hear: How do you incorporate improvisation into your artistic practice? How do you use it with your students? Which of these ideas or strategies resonates with you the most?

As always, feel free to reach out to me on Instagram or via email and let me know what you think.