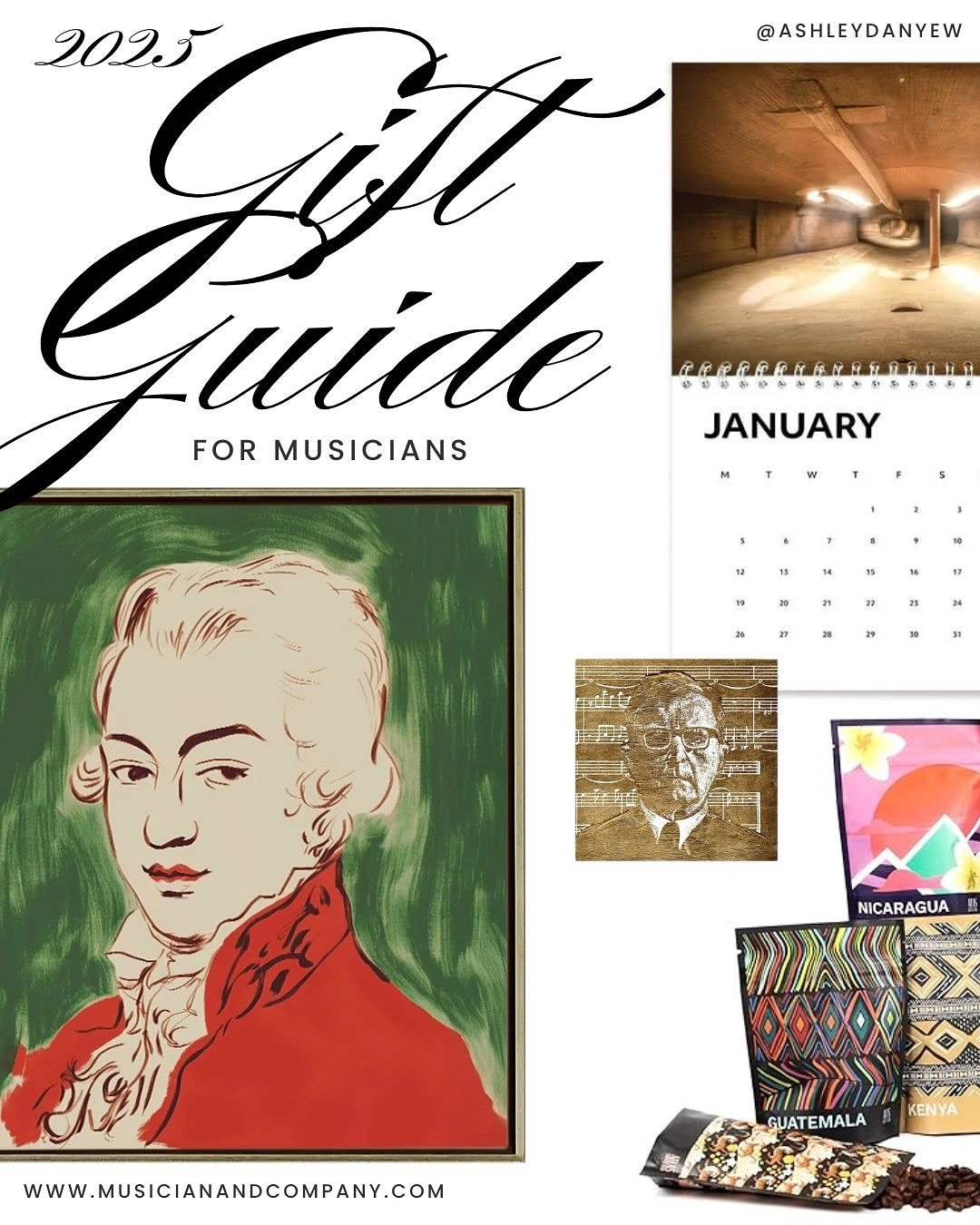

Resources Mentioned

*Disclosure: some of the links in this episode are affiliate links, which means if you decide to purchase through any of them, I will earn a small commission. This helps support the podcast and allows me to continue creating free content. Thank you for your support!

The Art of Practicing: A Guide to Making Music From the Heart (Madeline Bruser)

Learn Faster, Perform Better: A Musician’s Guide to the Neuroscience of Practicing (Molly Gebrian)

Join the Musician & Co. Book Club (it’s free!)

Sign up for the Lunch & Learn: Practicing Workshop on 11/10 (it’s free!)

Well-Tempered Clavier, Volume 1 (J.S. Bach)

Ep. 038 - The Secrets of Interleaved Practice: What We Can Learn From Cognitive Science

One of the things I love about teaching is that we can draw on many disciplines to make our work better—art, psychology, learning theories, and even neuroscience. Recently, I’ve been reading about what brain research can tell us about practicing and how we learn, and it’s fascinating.

Welcome back to our 2-part series on practicing.

In part 1, we talked about the art of practicing. I shared what I’m learning from Madeline Bruser’s book, The Art of Practicing, and how I’m carrying these concepts and strategies into my practice sessions and studio.

In this episode, part 2, we’ll explore Molly Gebrian’s book, Learn Faster, Perform Better. This book is all about the neuroscience of practicing: how we learn, process, and retain information. If you’ve been reading along with us in the Musician & Co. Book Club, you likely have some insights of your own, but I wanted to share what stood out to me and how it’s impacting my practicing and my teaching.

Speaking of that, I want to extend a special invitation—

Join me and fellow music educator, Jaclyn Mrozek of The Scrappy Piano Teacher Podcast for a free Lunch & Learn Practicing Workshop on Monday, November 10 at Noon ET. We’ll talk through some key takeaways from the book and experiment with applying them to real-life practice situations.

It’s okay if you haven’t read or finished the book—come for the highlights and get some new ideas for your own practicing and teaching. Click here to RSVP. A replay will be available to those who sign up.

Let’s get into today’s conversation.

Music Teaching & Learning Insights from Molly Gebrian’s Book

Good Practicing

I want to start by talking about what “good” practicing looks like. You can’t see me, but I’m using air quotes around the word “good.” Early in the book, Molly explains that we tend to think that practicing is about training our bodies, but it’s really about training our brains.

Good practicing is problem-solving.

This stayed with me. This is something you can say directly to your students in lessons. But how do we teach this mindset to our students? What does good problem-solving look like?

Here’s how Molly describes it:

Identify problem spots

Hypothesize solutions

Try out those solutions

Solidify the solution that works best

Move on to the next issue

That makes sense, right? It seems very logical and methodical, but there is a bit of guesswork involved—hypothesizing and trying things. And that involves taking risks and making mistakes. It’s part of the process.

So let’s talk about problem spots.

Problem Spots

Molly poses the question, “If you were to do a run-through right now in front of your teacher, which spots would you worry about? That’s where you should start [in your practicing].”

I’ve been using this approach in my practice sessions. As I mentioned in the last episode, I started a new practicing routine this fall: 30 minutes per day, 5 days a week. I’m working through the Well-Tempered Clavier, Volume 1, with one prelude and fugue each month.

At the beginning of the month, when the pieces are new, I spend the first few days analyzing, marking fingering, and studying the articulation. The next 7-10 days, I focus on the most challenging measures—HS practice, blocking harmonies, reviewing fingering and articulation, slow practice, listening for balance, and building good repetitions.

This is similar to Molly’s red, yellow, and green labeling strategy—something you could use with your students:

“Red sections are the ones in the worst shape. These are your emergencies. Yellow sections are those that don’t sound great, but aren’t an emergency. Green sections sound fine. Maybe they’re not perfect, but they’re acceptable for now. Start by working on your Red sections.”

Once those problem spots are more secure and consistent, I start piecing them together into larger phrases or sections, alternating between them during my practice session. This ties into two other concepts Molly explores in the book—overlearning and interleaving.

Overlearning

Overlearning is playing it correctly more times than you play it incorrectly. I talk about this a lot with my students and you probably do, too. “How many times did you play it wrong before getting it right?” Often, we’re not keeping track.

Molly gives the illustration of footprints in the snow—the more times you walk the same path, the deeper the footprints become. Neural pathways work the same way. But how many repetitions does it take to tell the brain, “Take this path, not that one?”

Research shows that practicing something a minimum of 50% more than the number of tries it took before you got it right the first time leads to much better retention. 100% is even better—if it took you 10 tries to get it right, do 10 more correct ones in a row to secure it.

But here’s the thing—your brain doesn’t know the difference between good repetitions and bad ones. I think it’s Marvin Blickenstaff who says, “Your fingers remember everything they play,” and I remind my students of this, too. Every time you repeat, you’re deepening a pathway.

Next time you (or a student) are struggling with a passage, think about how many correct repetitions overlearning requires.

Interleaving

The second concept I want to mention is interleaving.

I’ve talked about this on the podcast before, back in Ep. 038 - The Secrets of Interleaved Practice, but if you haven’t heard of this term before, here’s a quick overview:

Interleaving is a form of spaced practice that helps you be more nimble and flexible. It trains your brain to quickly reconstruct how to play well on the first try.

Unfortunately, most of us learn to practice the opposite way—through blocked practice. This is working on one thing for a block of time before moving on to the next. This is so ingrained in us that in one study, a group of pianists thought blocked practice was better, even though they could see that they performed better with interleaved practice.

Psychologists call this the “illusion of mastery,” which is such a great term, right?

Molly writes:

“Here is an uncomfortable truth: the measure of how well you practiced isn’t how it sounds at the end of your practice session. It’s how good it sounds the next day when you come back to it.”

I feel like I need to print this out and laminate it. How many times have you had a student come into their lesson and say, “This was so much better at home!” Or “I played this so well yesterday!”

A solution is to do more interleaved practice. Here’s an example of what this may look like:

A few weeks ago, I had a high school student who was working on a 4-bar introduction to a piece. He stopped and started, misplayed notes, questioned chords, and missed fingering. We broke it down, analyzed the chord progression, created a skeleton framework, and built it back up again.

Then, we moved on to another section in the piece. After a few minutes, I asked him to return to the intro and play it straight through—it went much better than the first time! We worked on something else for a few minutes, then I asked him once more to return to the intro. This gave him the opportunity to practice switching gears, to quickly reconstruct what he needed to play the intro successfully. I encouraged him to use this strategy in his practicing, as well.

Reflection

On this note, Molly talks about how important it is to let students self-evaluate before offering feedback. Research shows that students who received immediate feedback did far worse in performance than students who were given time to reflect first.

“It seems that when students are given immediate feedback,” she wrote, “They are not allowed to develop their own error detection abilities, and instead rely solely on the feedback of their teacher.”

It’s easy to jump in with reminders, corrections, or practicing strategies as soon as a student finishes playing, but lately, I’m reminding myself to pause—give them a moment to think first and draw their own conclusions. What if you waited 10 seconds longer before giving feedback in lessons—what would your student notice?

Internal vs. External Focus

When we do offer feedback in our teaching, Molly says it’s best to keep the focus external.

“Focusing on what your body is doing (having an internal focus) is not as effective as focusing on something outside your body (having an external focus). . .When we try to control our actions by paying attention to what our body is doing, we get in the way of automatic processes that would normally regulate and coordinate the motion on their own. . . .When we focus on something outside of our body, however, we allow the motor system to coordinate the action in an automatic way.”

But is it really realistic to do this all the time? Sometimes, you need to say, “Keep your wrist lifted here” or “Relax your shoulders.” Right? Right.

Molly explains the key is to keep the focus on the effect of the action, so the body is free to coordinate the movement without the mind stepping in to control it. A good way to do this is to use analogies.

For instance, “Think about a sleeping pencil resting on your arm as you play” or “Pretend you’re swimming in the lake. Your elbows are bobbing loosely in the water, and you’re running your fingers lightly along the glassy surface of the water.” See how this addresses the physical coordination while keeping the focus on something external—the sleeping pencil or the water?

This ties in well with the last section I wanted to discuss today—developing the inner ear and an internal sense of steady beat.

Audiation

We know that developing the inner ear is a vital part of our work as music teachers. But it’s more than having students listen before playing or asking them to play something silently. It’s about learning to hear music with understanding, with no sound being present.

Scientists call this auditory imagery. Musicians call it audiation.

Molly cited one study that found that when students were learning to hear and play intervals, singing, then playing them was more helpful than just singing or playing them alone. Isn’t that interesting? This indicates we need to be intentional about connecting the music we hear in our heads to the music we’re creating.

One thing I’ve been trying in lessons lately is having students sing before they play.

Sing the melody, then the bass line (often with solfege).

Play each part separately.

Sing one hand and play the other before playing hands together.

First of all, this is a great coordination challenge and a useful skill to develop. And second, their hands-together playing is always better and more confident after taking these steps. It seems to build their awareness of the two independent parts and how they fit together.

Sense of Steady Beat

In terms of developing an inner sense of rhythm, Molly noted that a metronome can show you where you’re rushing or slowing down and can illustrate where rhythmic figures lie in relation to the beat.

But it won’t help you develop a sense of steady beat. To do that, you need to engage your whole body (or at least your vestibular system, in the inner ear).

One of the best ways to improve an inner sense of pulse is to have students step in place or walk around the room while singing or playing. This is a hallmark of the Dalcroze approach and something I’ve been intentional about incorporating into lessons more recently. Molly notes that even swaying back and forth on the bench or in a chair can help, as it activates the vestibular system.

One thing I’ve noticed with some of my students is that when I ask them to step the beat or walk with the steady beat while I play, they stiffen their legs and walk like a robot or move awkwardly. Do your students do this, too? It doesn’t always seem natural or relaxed. Molly mentioned encouraging students to walk or move musically: “Taking deeper steps on strong beats, more shallow steps on weak beats.” I think sometimes we need to help students embody musical experience.

One way to do this is to move with them, or create an environment where they can move with their peers. Molly explained, “Everyone is helped in their sense of pulse when someone else is also moving alongside them, but especially younger children.”

I’m curious to hear your thoughts & ideas on this topic:

How do you incorporate movement activities into your lessons or group classes? Do you have any favorite games you like to play?

Conclusion

Practicing isn’t just about putting in the hours; it’s about working with the brain, not against it. And the more we understand how learning really happens, the better teachers and musicians we can become.

I hope you enjoyed this mini-series on the art and science of practicing, exploring concepts and insights from Madeline Bruser’s and Molly Gebrian’s inspiring books. Learn Faster, Perform Better is one of my favorite books I’ve read this year, and also maybe the most tangible. I’ve really enjoyed taking some of these concepts into my daily practice sessions to test them out and then bringing them into my studio—my teaching lab.

I hope you’ll enjoy doing that, as well.

Don’t forget to sign up for the free Lunch & Learn workshop I’m hosting with Jaclyn Mrozek next week. Think part book club discussion, part practicing workshop. Get more details + RSVP here.