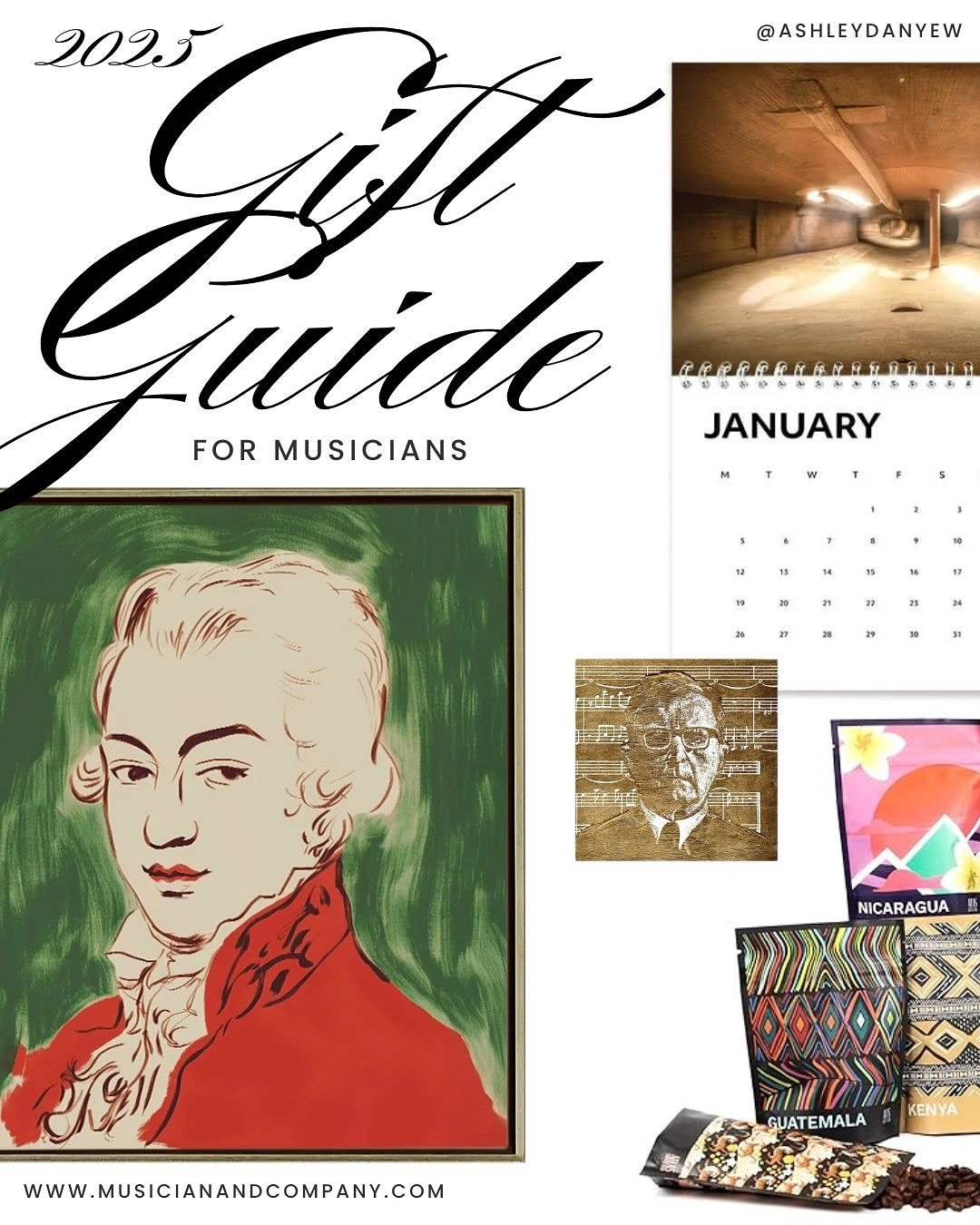

Resources Mentioned

*Disclosure: some of the links in this episode are affiliate links, which means if you decide to purchase through any of them, I will earn a small commission. This helps support the podcast and allows me to continue creating free content. Thank you for your support!

“This Is What Diversity Sounds Like” by Linda Holzer (Piano Magazine)

3 Sketches for Little Pianists (Florence Price)

Expanding the Repertoire: Music of Black Composers, Levels 1 and 2 (compiled & edited by Dr. Leah Claiborne)

Five Animal Sketches (William Grant Still)

Portraits in Jazz (Valerie Capers)

Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, Vol. 1 (compiled & edited by William Chapman Nyaho)

February is Black History Month—a time to honor and celebrate the contributions of African Americans. As a music teacher, this prompts me to pause and evaluate what I’m teaching, but also why. I ask questions like:

How much diversity is present in my students’ method books and repertoire?

Which pieces should we skip due to their complicated history?

How can I make more thoughtful, informed choices about the music I put in front of my students—choices that are pedagogically sound and historically responsible?

A few years ago, these questions led me to design a Blues Composition Project in my studio. We learned the blues progression in different keys, studied examples from the repertoire and listened to recordings, and experimented with accompaniment patterns. By the end of the project, each student had their own unique blues composition and a performance recording. You can hear a few examples and learn more about how I organized this in Ep. 045.

This year, I want to focus more on the existing repertoire and the creators behind it. In this episode, I’m going to introduce you to seven Black composers of elementary and intermediate piano repertoire.

Introducing Black Composers Through Piano Repertoire

Florence Price

Florence Price (1887-1953) grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, like William Grant Still (she was eight years older). She began composing at an early age and had her first piece published at age 12 (source: LAPL). At age 15, she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music, studying with George Chadwick. She graduated in 1906 and, by 1910, was head of the music department at Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia.

In Piano Magazine, Linda Holzer describes Price’s compositional voice as a blend of two worlds: “the African-American musical heritage of her. . .childhood (spirituals, gospel, blues, jazz), and the European art music influences from her formal studies.” Holzer notes that Price’s “poignant melody, expressive harmony, and thoughtful phrasing” position her as a composer-pianist in the lineage of Brahms.

Due to increasing racial tension in the South, the Price family moved to Chicago in 1927. Following the economic crash and her subsequent divorce, she supported herself and her two daughters by playing for silent films, writing radio commercials, and organizing concerts (source: LAPL). During this period, she completed her First Symphony, which won first prize in the 1932 Wanamaker music contest and was premiered by the Chicago Symphony in 1933—making her the first African American woman to have a work performed by a major American orchestra. She earned a postgraduate degree from the University of Chicago the following year.

Price wrote more than 300 works, including symphonies, chamber music, art songs, and piano pieces. I had two students play “Criss Cross” as a duet last year, which was really fun. It’s similar in style to “Hungry Herbie Hippo” in Piano Safari Level 1. It appears in RCM Preparatory A Repertoire and A Collection of Florence Price’s Piano Teaching Music, Vol. 2, available from Classical Vocal Reprints. I also love “Bright Eyes” and “A Morning Sunbeam” for Level 1-2 students, which are from Price’s 3 Sketches for Little Pianists, available on IMSLP. More advanced students often enjoy “Ticklin’ Toes,” which appears in RCM Level 7 Repertoire and Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, Vol. 1.

Blanche K. Thomas

Blanche K. Thomas (1885-1977) was an award-winning composer and educator. In 1928, she became one of the first African-American students to graduate from Juilliard, earning a Bachelor’s degree in Music Theory. She also studied choral conducting at the Westminster Choir School.

In 1932, she founded what would eventually be called the Thomas Music Study Club—a mixed ensemble of youth who studied and performed the music of African American composers. They performed at several New York venues, including Carnegie Hall and the New York World’s Fair. In addition, Thomas maintained an independent music studio (piano, voice, and related subjects) and served as a church school music director (source: NYPL).

Her collection, Plantation Songs in Easy Arrangement for the Piano, features music at Levels 1-2, several of which can be found in Expanding the Repertoire: Music of Black Composers, Level 1, compiled and edited by Dr. Leah Claiborne.

Leah Claiborne

Dr. Leah Claiborne is a pianist, scholar, and educator. She is Director of DEI at Piano Inspires, DEI column editor for MTNA, and contributing writer for Music by Black Composers. A graduate of the Manhattan School of Music, she received her Master’s and DMA from the University of Michigan. She currently teaches at the University of the District of Columbia, where she serves as coordinator of keyboard studies and teaches the History of African American Music.

Dr. Claiborne is the editor of two volumes of Expanding the Repertoire: Music of Black Composers, published by Hal Leonard. The Level 1 book includes 16 pieces for elementary to upper elementary students, and Level 2 includes 14 pieces for early intermediate to intermediate students. Composers include Ulysses Kay, Ignatius Sancho, Hale Smith, Blanche K. Thomas, and several of her own compositions. She is included as a composer and performer on the 2025 release, Arise & Shine: Music by Black Composers for Kids.

William Grant Still

William Grant Still (1895-1978) lived at the same time as George Gershwin and Aaron Copland, but was raised in the Jim Crow South—in Little Rock, like Florence Price. Their families were part of the same intellectual, middle-class African American community (source: LAPL). Still grew up listening to classical records and playing the violin, oboe, clarinet, and other instruments (source: Copper, Issue 176).

Still attended Oberlin and studied music composition with Edgar Varèse. He soon realized that 20th-century, avant-garde, electronic music was not his style; he preferred to write music drawn from the European classical tradition, but informed and shaped by the gospel and folk music of his heritage. So he transferred to NEC to study with the more traditional George Chadwick (who Florence Price studied with a few years earlier).

Still became the first African American to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra. His Afro-American Symphony was premiered in 1931 here in Rochester, NY by members of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra, under the direction of Howard Hanson, who was the Director of the Eastman School of Music at the time (source: Eastman School of Music). Still was also the first African American to conduct a major symphony in the South, conduct a major American network radio orchestra, and have an opera produced by a major American company.

His Five Animal Sketches is a collection of short, intermediate-level piano pieces, available through www.williamgrantstillmusic.com. You can hear recordings of all five pieces on the Arise & Shine record.

Ulysses Kay

Ulysses Kay (1917-1995) took piano lessons growing up, and later played the violin and saxophone. He sang in the glee club, played in the marching band, and was a member of his high school dance orchestra. He attended the University of Arizona for his undergrad, during which time, he had a brief visit with William Grant Still, which set him on the road to becoming a composer. He attended the Eastman School of Music for his Master’s, studying music composition with Bernard Rogers and Howard Hanson.

The next summer, 1941, Kay won a scholarship to Tanglewood and studied with Paul Hindemith. Then, he won a scholarship to Yale for the next academic year so that he could continue his work with Hindemith. He served in the U.S. Navy during WWII, playing in the Navy Band. After the war, he received a year-long fellowship for creative work at Columbia. He became a Fulbright scholar and won two "Prix de Rome” awards.

Three of his 10 Short Essays for Piano are published in the Expanding the Repertoire books. No. 6, “Make Believe,” is listed on the Level 2 repertoire list in the 2022 RCM Piano Syllabus.

Valerie Capers

Valerie Capers (b. 1935) is an African-American pianist, composer, and educator. She was the first blind graduate of the Juilliard School. She was nicknamed “Ears” and received her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees there (source: AWFC). She taught at the Manhattan School of Music and has performed with Dizzy Gillespie, Ray Brown, and Wynton Marsalis, among others. Her solo piano collection, Portraits in Jazz was written for students who want to play something not “classical” (source: AWFC) It’s a tribute to great jazz musicians such as Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, and Thelonius Monk.

My intermediate students have enjoyed “Ella Scats the Little Lamb,” “Waltz for Miles,” “Billie’s Song,” and “Sweet Mister Jelly Roll.” “Sweet Mister Jelly Roll” is also published in Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, Vol. 1 and RCM Level 6 Repertoire. Other pieces in this collection are included on the Level 8 and Level 9 repertoire lists in the 2022 RCM Piano Syllabus.

Oscar Peterson

Oscar Peterson (1925-2007) was a legendary jazz pianist and composer. Born in Montreal, he produced over 200 recordings during his lifetime, with appearances by Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others. He won eight Grammy Awards and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award from the Recording Academy. Standing at 6’3” and weighing 250 lbs., sources say he had large hands and could easily reach an 11th.

I enjoyed studying “Jazz Piece No. 2” with an intermediate student earlier this year. It’s published in the RCM Level 6 Etude book. It’s kind of a bridge between classical and jazz music and I used it as a jumping-off point for improvisation exercises and assignments with this student throughout the semester. For instance, “In the second line, keep the bass line the same, but create your own variation in the right hand,” or “Block the harmonies in the first line and create an improvisation based on this progression.”

Conclusion

Repertoire shapes musical identity. It informs students’ musical understanding, inspires their creativity, and broadens their perspective and worldview. I hope this episode gave you a few new composers to explore and a few new pieces to try (or listen to).

As always, I’d love to hear from you: What composers are you studying this month, and which pieces are resonating most with your students?